A Different Kind of Culture Shock

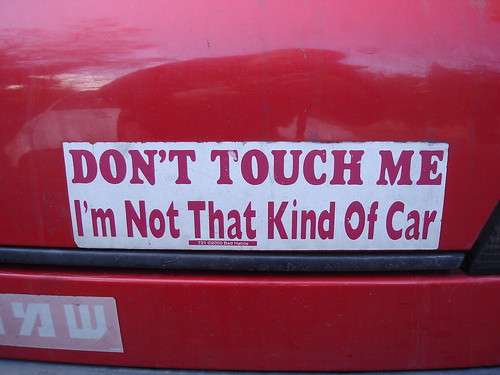

Over time, Israeli society has become more sensitive than ever before to the issue of smoking in public places. Several decades ago, smoking was permitted almost everywhere—on buses, in restaurants, in workplaces. Today, after many efforts by various groups, it no longer is. The laws against smoking in public places and in workplaces are much stronger, and although enforcement is still far from ideal, it is much better than it was.

However, much still depends on where you go. In one of the buildings where I work, for example, the owners ignored the anti-tobacco laws even after they were passed and continued to allow approximately fourteen large, ugly, sand-filled ashtrays to remain in the building. After having spoken to the building manager many times and heard his promises to remove them—promises that remained unkept for months—I finally contacted the municipality. Only then did the owners remove the ashtrays. But the smoking persisted, and does in various degrees to this day.

Last August, a local college opened a branch in the building. It happens to be the branch for Arab students. At first, many of the students smoked in the hallway outside the college’s office and classrooms. In addition, both students and staff smoke in branch’s front office almost all the time. The smoke spills into the corridor, forcing anyone who passes by to breathe it in.

Over the past several months, I asked the people in charge many times to deal with the smoking problem. They refused, and continued to smoke there in full view of everyone. Today, after breathing in one lungful too many, I decided that it was time to call the municipality to complain. The woman I spoke with promised to send inspectors out as soon as possible.

When I left work a little while later and got into the elevator, I encountered the two inspectors that the municipality had sent. They had arrived, witnessed the people smoking, and fined the branch’s management five thousand shekels.

The director, who was furious, got into the elevator with us and leaned his face close to mine. “I know I have you to thank for this,” he told me. “I just got a fine of five thousand shekels, all because of you. You can be happy now.”

“I’m not,” I told him, looking him straight in the eye. “I’m not happy about it at all.”

“What you did was racist,” he said, as the elevator reached the ground floor and we got out. “It was a racist act. I’ll make sure that you leave this building, and I’ll have you in court!”

I didn’t care much about his threats to make me leave the building, as he put it, or to take me to court. After all, what grounds would he have to sue me? I had acted within my rights according to the law, and I have a solid record of acting against smoking in the building regardless of the smoker’s racial origin. Still, his accusation of racism bewildered and even shocked me. “Racist?” I asked him. “What has this got to do with racism? Please, let’s talk about this. Please explain to me why what I did was racist.”

“People smoke here all the time,” he said, “and I’m sure that you never called the municipality about them.”

“Actually, I did,” I told him. “I reported a Jewish-owned business a while back, and its owners were fined five thousand shekels, too.”

“We’re a non-profit organization that works for co-existence,” the director continued. “We don’t have five thousand shekels to pay such a fine. You’ve caused us terrible damage. How could you do this to us?”

“It’s your own behavior that’s responsible,” I said. “I asked you many times not to smoke in the building. I explained that it was harmful and against the law, and you chose to do it anyway.”

“There’s something else,” he said. “The inspectors were two men, and they entered a classroom where twenty young women were sitting. Since only women were in the classroom, they had taken off their head coverings. As soon as the men entered, they scrambled to put them back on as quickly as they could. A few of them started to cry. I can see that you have a conscience and that you understand about modesty. Do you have any idea how much this hurt them?”

“Yes, I do,” I said, thinking about the male police officers and workers who move freely about the women’s section at the Western Wall. “And I regret with all my heart that it happened. I never would have wanted it to happen, and I had no idea that it was going to. It sounds like the inspectors behaved insensitively, and that was wrong. Nevertheless, you knew that smoking in the building was harmful and against the law, and you did it anyway. That is a separate issue. It has nothing to do with racism or modesty.”

Gradually, the branch director calmed down. I think that in the end, we understood each other better. We ended the conversation by wishing each other well, and that was encouraging.

I’ll see what happens this coming Sunday.