God’s Gatekeepers

I’ve posted before about the disparity in size between the men’s and women’s sections of the Western Wall. This shot, which I took when I was there yesterday, shows it quite clearly.

As I’ve written before, I have no problem with the idea of a mehitza—a divider between men and women—at prayer. I like the privacy that it gives me. But I do have a problem with a divider that creates such an unequal situation as the one at the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest accessible site. Others have a problem with it, too, and are now beginning to speak out. I would have been at the protest candle-lighting in the Kotel Plaza during Hanukkah, but I had to work.

The inequity in space allocation extends indoors as well. The men have a great deal of indoor space that allows them to approach the Kotel directly. The women have much less—in fact, hardly any, and a good portion of what they do have is restricted (see below). Therefore, if women want to pray with full access to the Wall itself, they must crowd into what I’ve come to call the Incredible Shrinking Women’s Section in all weather conditions: punishing sun in summer and cold and rain in winter.

At the far right of the Kotel, up a flight of stairs, is a small room where women may pray indoors. I call this tiny room “the classroom” because that is what it looks like to me: a tiny classroom that could seat perhaps ten people comfortably. Many more crowd inside to avoid the rain:

So I decided, as I have done before, to go inside the Western Wall Tunnels area, where there are both official and unofficial places for women to pray.

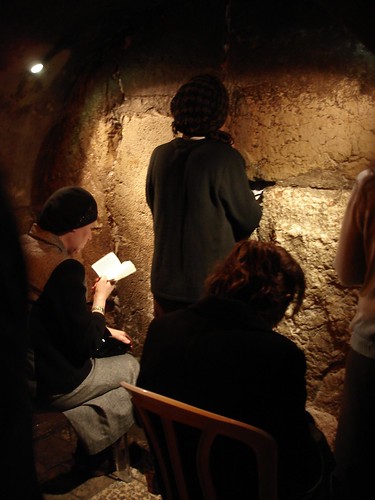

The photo below shows an “unofficial” spot along the passageway that is reputed to be directly opposite the spot on the Temple Mount where the Holy of Holies stood. Women pray here as a matter of course. The spot is also along the route of the Western Wall Tunnels tour, so they are frequently disturbed by tour groups, as we’ll see below.

By contrast, directly above this spot is a beautiful, bright, well-appointed synagogue. Women can pray there if there are no men inside... but if men are present, they will ask the women to leave. When one asked me to yesterday and I refused, he took no action, saying only “Be healthy,” a common form of dismissal here. Here, in a photo that I took a few months ago, a man reads from an open Torah scroll in the Ark inside this synagogue:

The official space that has been allocated to the women inside the Kotel tunnels is a balcony enclosed by one-way glass that has no direct access to the Kotel itself. Earphone jacks have been built into the walls so that women relatives of boys celebrating their bar mitzvah will be able to hear the service from inside.

As with the outdoor section, another disparity prevails: men may enter the women’s section, but no woman may enter the men’s section for any reason. Men’s space is sacred space. Women’s space is not. Here, a worker enters the women’s section in order to gain access to a supply closet that is located there, directly inside the prayer area.

Back outside, near the spot along the tour route where women pray, a tour group passes by:

The flash makes the area look much brighter than it actually is. The photo below reflects the amount of light more accurately. Oil lamps burn opposite the gate, relieving the dimness somewhat:

When the tour group passed by, the guide told them that they could pray there if they wished. They stopped right behind the women who were sitting there and praying. One of the men on the tour, pictured at the left of the photo, recited Psalm 130 in melodic Hebrew, in Mizrahi style. I got the feeling that if he was not religiously observant, he was at least traditional and familiar with the sources and prayer customs, probably from a young age. Yet there he was, praying right alongside the women.

I had to do quite a lot of work in order to reach that spot myself. When I tried at first, two guards barred my way. I was surprised; I’d never had a problem getting there before. I watched, incredulously, as the guards let other individuals in, both men and women, even as they told me that I could go no further and one of them went so far as to block me with his body. When I asked why they were allowing the others in and not me, the guards answered that the others had permission. “How do I get such permission?” I asked. They told me to go back to the guard at the front desk. I did.

At first the guard did not want to let me in, explaining that the spot was open to the general public only between the hours of 3:00 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. At all other times, he said, it is closed to the public, open only to tour groups and to individuals by special permission. (I did not see this information posted anywhere in the Western Wall Plaza.) I pointed out that other women were praying there and that the guard had allowed other people inside as I watched. The guard at the front desk said that those individuals had received special permission. I persisted, and eventually he gave me that permission... when I had pleaded enough.

“You have five minutes,” he told me. “There are cameras there, all over.”

Good grief, I thought. What does this man think I’m going to do there?

Here is the gate where I was stopped. (I note, with irony, the presence of the Israeli flags in the photo. The Western Wall is supposed to be a national site, open to everyone equally.)

Here are the feet of the guard who stopped me. The edge of the book that he is reading—presumably a prayer book or book of Psalms—can also be seen:

When I was on my way out, the guard at the entrance stopped me again and began to reprimand me, saying that he had done me a great favor in letting me into the tunnels. “There were other women there too,” I pointed out. He bristled. “Are you arguing with me?” he asked aggressively. “Do you want to argue with me?”

“You let them in even though it’s well after 8:30 in the morning,” I told him. “They have problems,” he said, indicating that he had let them in as a favor—as he had done with me. “I turn lots of people away. But I let them in. And I let you in.”

As I listened to this man, who evidently fancied himself God’s own gatekeeper, I grew more and more shocked and disgusted by his attitude and by the unfair and arbitrary way in which the regulations were enforced. Finally, I could take no more. “Enjoy your power,” I said, and walked away. He called after me, “Is that how you talk to me? Is that how you talk to me?”

Now, before my half-dozen readers jump all over me: I know that I should have kept my mouth shut. But I simply couldn’t bear his arrogance for one moment longer.

When I told this story to an Israeli-born friend, she remarked, “Eved ki yimlokh” (a servant who becomes a ruler; Proverbs 30:22). Israelis routinely use this phrase to express their disgust with petty bureaucrats on power trips.

Back outside, the sign does not mention a word about when the tunnels are open to the public for prayer:

Here are the rules to be observed in the Western Wall Plaza. No word there about any 3:00 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. opening times either:

Up along the plaza is a passageway for men only. I can’t help wondering who funded it.

The entrance to the office of the administrator in charge of the Western Wall, often erroneously referred to as the rabbi of the Kotel, as in this sign:

A charity box located near the women’s section that also contains the mistaken phrase “rabbi of the Western Wall.” (Someone made a donation just as I was taking the photo.)

But as I was leaving, I saw something lovely. In the middle of the plaza, a young man was on one knee before a young woman. Both looked delighted. As I passed by, I flicked a quick and careful glance at them just at the moment that the young man was putting a ring on the young woman’s finger. I walked on, then turned around. The young man and woman were hugging, and the woman was standing on tip-toe to reach him. Then a friend joined them, and they left the plaza. Here they are, from the back and from a distance: